Excerpts from Making History: The Struggle for Gay and Lesbian Equal Rights, 1945-1990* by Eric Marcus

Dr. Judd Marmor [Full Chapter]

When the American Psychiatric Association’s Board of Trustees voted to remove homosexuality from its list of mental disorders in late 1973, many commentators, from inside and outside the profession, claimed that the APA had capitulated to extreme pressure from gay activists. Certainly many gay men and women had exerted pressure, conducted protests, and made appeals in the three years leading up to the decision. But there were also respected psychiatrists within the organization who worked over the years to effect the change.

One of those people was Judd Marmor, a Los Angeles psychiatrist and psychoanalyst, who began moving away from the prevailing sickness theory in the 1950s. Dr. Marmor was not willing, initially, to fully accept Dr. Evelyn Hooker’s 1956 assertion that homosexuality was not a mental illness. Within a few years, however, he came to believe that the psychiatric profession was mistaken in its assessment of homosexuality, and by the early 1970s, he had become a leading voice in the campaign to reconsider the classification.

Dr. Marmor maintains his office in Westwood, an affluent neighborhood adjacent to UCLA. A vigorous 80, Dr. he continues to see patients and to play tennis three times a week. He’s a small man, trim, completely bald, and deeply tanned. Dressed in a well-tailored suit, Dr. Marmor pointed out his many awards on one wall of his office, particularly those bestowed by gay organizations.

≈

After the war—World War II—I saw homosexual patients who wanted to change their sexual orientation. At that time I used to try to help them change. We all used to think in those days that psychoanalysis could cure everything from chilblains to homosexuality. But I wasn’t too successful. Some were able to function bisexually, but most of them remained gay. The gay men who came to see me were mostly in the literary field or in the show business field. They were intellectual. They were bright. They did not consider it a disgrace to be analyzed. All their straight friends were being analyzed too. It was the thing to do in the fifties. I saw a few lesbian women, too, but they were married and were mostly concerned with making their marriages work.

The gay men I saw were for the most part caught up in the common myth that it was bad to be gay and that if they possibly could they ought to try to be heterosexual. This was before the gay rights movement, you understand, and before gays thought in terms of coming out and functioning on their own, openly. So, although I didn’t feel it was bad to be homosexual, I was sympathetic to their wishes to try to become straight if they could.

We did a lot of talking about what it took to “make” a girl, to win a girl, to seduce a girl, to participate in a mutual seduction. And we dealt with their anxieties, if they had any. Now, many of them were capable of functioning heterosexually, but they said, “It just doesn’t feel the same to me. I just don’t enjoy it as much.” We went through the usual thing of trying to understand why they couldn’t enjoy it. In those days we still assumed all explanations lay within the family dynamics. The fear of competing with the father. The incest barrier. Castration anxiety. God, we used to work that myth of castration anxiety! Not that people don’t have castration anxiety, but I understand it in very different terms now. It’s a symbol, not a fact. In those days we used to think as though it had literal meaning—almost. My patients understood these things, but it didn’t usually change matters for them.

I very quickly realized—since I wasn’t judgmental about them being gay—that if I couldn’t help them achieve heterosexuality, which they assumed they wanted, that my job was to help them accept their gayness and live effectively within that scheme of things. Usually I ended up saying, “Look, there’s nothing bad about being what you are. Just live your life and don’t be ashamed of it and let’s deal with whatever your problems are within the context of your gayness.” So very early in my practice, even in the 1950’s, I was working in that manner.

≈

The first time I heard Dr. Evelyn Hooker make the statement that homosexuality was not an illness, I wasn’t prepared to go all the way. This was in 1956, when she presented her study of gay men. I was sympathetic to what she was saying, but I wasn’t totally convinced. I still had a feeling that it was a developmental deviation, but I did not think that we ought to be judgmental about homosexuals. We were also making a lot of unwarranted assumptions about the so-called homosexual personality. But I still wasn’t ready to assume that there was something other than a developmental deviation involved in it.

Now, I had met Dr. Hooker before she presented her study, and liked her. So when I heard her making these statements about homosexuality, I saw her not as a stranger, but as a good friend whom I admired and whose work I knew and respected. I felt that there certainly was research to be done in that area, that we were taking a lot for granted that we didn’t understand.

Within a few years, I began to work on my own book, the first of two books that I did on homosexuality. It’s called Sexual Inversion, a title I hate. My publisher insisted that I have the word sexual in it. He wouldn’t let me call it just Homosexuality, which I wanted to. That title had been pre-empted by too many other books. So we called it Sexual Inversion: The Multiple Roots of Homosexuality.

In that book I made the statement that it was hard to believe that people would be homosexual in the face of the enormous social opprobrium they had to live with, unless there were powerful developmental reasons for it. At the time, I still believed that. The research hadn’t yet been done on the constitutional factors—not necessarily genetic, but intrauterine, pre-natal—that might create the pre-disposition to homosexuality.

I pointed out, though, that the assumption that homosexuality was an illness was based on a skew sample because psychoanalysts saw only disturbed homosexuals in their offices. I said in the book that if we made our judgments about the mental health of heterosexuals only from the patients we saw in our office we’d have to assume that all heterosexuals were mentally disturbed.

One of the reasons I wanted to do this book was that I was appalled by the stereotypic generalizations being made about homosexuals in the various psychoanalytic meetings I was going to. I was still a young analyst, but I’d go to meetings and I’d hear about the homosexual personality and about the fact that homosexuals were vindictive, aggressive, couldn’t have decent relationships, were not to be trusted. All terribly nasty, negative, disparaging things. I knew gay men and women. This just didn’t make sense to me. I felt we were making generalizations about people who were really very different from one another, just as heterosexuals are. That’s one of the points I attacked strongly in my book, that this stereotyping of a group really concealed a discriminatory prejudice. I don’t think the word homophobia had yet been coined.

I stated that our attitudes towards homosexuality were culturally determined and influenced, which was a big step forward in the analytic profession. It was considered a relatively revolutionary statement, coming from a member of the American Psychoanalytic Association.

I got heat from my classical analytic friends, but at meetings of the American Psychiatric Association, psychiatrists began to come up to me and say, “Look, I want to tell you how much I appreciated your book. I’m gay.” Gradually I came to know a large number—much larger than I had known before—of gay men, particularly, but also some lesbians. My knowledge and experience of homosexuality, then, was broadened by precisely the thing that I had commented on in my book: the fact that psychoanalysts didn’t know enough gay people outside the treatment community who were happy with their lives, who were satisfied and well-adjusted.

≈

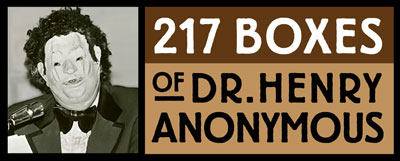

We had some very dramatic confrontations over this issue during the early 1970’s. The gay liberation movement became very vocal and very assertive and began to appear at American Psychiatric Association meetings and demanded a voice. These were the days in which homosexuality was being treated by aversive therapy, by shock therapy and things like that. The gay people were justly very angry at that. They demanded that they be given a session in which they could present their views. At this session I spoke on a panel with a number of other people. There was the head of the lesbian movement at that time, Barbara Gittings. Frank Kameny was there. Another psychiatrist was on the panel, from Philadelphia. He wore a mask and spoke into a microphone that concealed his voice, and admitted that he was gay. This was an unheard of thing. It was a very dramatic session with this fellow speaking with a grotesque mask on. And I spoke out very strongly.

Then, a year later we had an official debate, the debate about the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, which listed homosexuality as a mental illness. On the platform representing various points of view were myself, Richard Green, Robert Stoller, Charles Socarides, and Irving Bieber. This was a very, very dramatic debate, which was attended by several thousand psychiatrists at one of the conventions of the American Psychiatric Association. I think by-and-large we won the debate.

At any rate, shortly after that, the debate got into the board of trustees of the APA. Different points of view were presented and the board made its decision. This was all detailed in a book by Ronald Bayer, Homosexuality and American Psychiatry: The Politics of Diagnosis. The only thing I disagree with Bayer on is that he assumes that the attitudes of the psychiatrists were developed under pressure from the gay community. That’s not entirely true. I don’t in any way want to minimize the importance of the gay liberation movement, but there were people like myself and Evelyn Hooker and others who were independently developing their views about the wrongness of our attitudes toward homosexuality. I think Bayer either didn’t understand that or underplayed it.

After the Board of Trustees made its decision to remove homosexuality from the list of psychiatric illnesses, Socarides and Bieber and others were furious. They were convinced that the majority of the psychiatrists in the profession would be aghast at this decision, so they forced a vote of the general membership. The board’s decision had not been made by a vote, but after considerable scientific exploration. To the dismay of Socarides and Bieber, a majority of the psychiatrists voted to support the board’s decision. The vote was 58 percent to 37 percent, with 3 percent abstaining. The remaining 2 percent didn’t vote.

I wasn’t totally surprised by the outcome, but I was a little worried before the vote as to whether the board’s decision would be supported. At the point the vote was taken, I was already a candidate for president of the American Psychiatric Association. I urged a positive vote. I won the election, too, so there may have been some connection there.

The removal of homosexuality from the list of psychiatric illnesses was very significant because it meant that people who wanted to discriminate against homosexuals could no longer say, “Look, the psychiatrists call it an illness. It’s considered a sexual perversion. And we can’t have people who are sick working for us. We’re entitled to stop them from being school teachers or from hiring them.”

We didn’t merely remove homosexuals from the category of illness, we stated that there was no reason why, a priori, a gay man or woman could not be just as healthy, just as effective, just as law-abiding and capable of functioning, as any heterosexual. Furthermore, we asserted that laws that discriminated against them in housing or in employment were unjustified. So it was a total statement, and I think it was a very significant move. Shortly after that, the American Psychological Association and the American Bar Association came out in support of homosexuals. It was an important step that we took.

≈

The gay psychiatrists who I came to know ultimately formed a group within the American Psychiatric Association that they called the Gay PA. It was originally closeted, but it finally became what is now the Caucus of Homosexually Identified Psychiatrists. It’s an open organization with a representative in the Assembly of the American Psychiatric Association. It’s a very effective representative for the gay and lesbian community. I have gone to most of their annual meetings and was honored at their last one. They are a significant part of the association, even though there are still many psychiatrists and psychoanalysts who remain closeted.

Unfortunately, many psychiatrists still believe that homosexuality is a mental illness caused by fear of the dominant mother, competing father, et cetera. I would say that maybe a third of the psychiatrists in the United States and maybe half of the psychoanalysts, and possibly even more, still believe it is an illness. They haven’t accepted the fact that it’s not.

The American Psychiatric Association is not the gestapo. It can’t force psychiatrists to change their minds about this. It has simply taken homosexuality out of its official diagnostic and statistical manual, so it’s no longer listed as an illness.

That’s why the struggle still goes on. These psychiatrists and psychoanalysts are very apt to say, “I can help you change and I will try.” Particularly among the classical Freudian psychoanalysts there is a strong feeling that this can be accomplished. Many younger analysts, more progressive ones, will examine the reasons for the person wanting to change, to see whether it’s a genuine wish that has real strength and motivation behind it or whether it’s a product of society’s disapproval. In which case, many of them will say, “Look, why do you want to change?”

This issue is not totally resolved by any means, although there is gradually, in my judgment, a constantly increasing body of information which fortifies the position that the American Psychiatric Association has taken. But I think there’s a great deal of unconscious homophobia. People grow up feeling that homosexuality is something bad, something frightening, something alien. When they become professionals they rationalize that into a need to change it, a feeling that it ought to be changed, that people ought not to be content to be homosexual. That then plays into their professional activities and theoretical perceptions.

As far as my role in this movement is concerned, I’m very proud of what I’ve done. I think it’s one of the good things that I’ve done as a psychiatrist. I only regret that I didn’t come to it sooner.

Barbara Gittings & Kay Lahusen [Excerpt]

Barbara:

Besides the Library Association, I was also very involved, along with many other people, in efforts to get the American Psychiatric Association [APA] to drop its listing of homosexuality as a mental illness. Psychiatrists were one of the three major groups that had their hands on us. They had a kind of control over our fate, in the eyes of the public, for a long time.

Kay:

You don’t realize what it was like back then. They were the experts. They said we were sick, and that’s what most people believed.

Barbara:

Because gay people were considered mentally sick, people turned to psychiatrists for answers to the question of homosexuality. What causes it? What can we do about it? How can we eliminate it?

Kay:

When we were spoken of, people wanted to hear what a psychiatrist had to say. They didn’t care what we said. We had to change all that.

Barbara:

Religion and law were the other two groups that had their hands on us. So besides being sick, we were sinful and criminal. But the sickness label infected everything that we said and made it difficult for us to have any credibility for anything we said for ourselves. The sickness issue was paramount.

Kay:

It was Frank Kameny who said that we had to proclaim, in the absence of valid evidence to the contrary, that we were not sick. And the burden of proof rested on those who called us sick.

Barbara:

Well, it made great sense to us that we shouldn’t wait around for the experts to declare us normal. But in the early days of the movement many gay people believed they were sick. And even those who didn’t agree still felt that we had to wait for the experts to change their minds. We were supposed to wait 50 or 75 years for the experts to come up with the answer that we weren’t sick? Frank and others started to feel that we couldn’t wait.

Our confrontation with the American Psychiatric Association began in May 1970, when a large group of feminists and a few gays invaded a behavior therapy meeting at the American Psychiatric Association’s convention in San Francisco that year. I wasn’t there, but from what I understand, they disrupted the meeting and said, in effect, “Stop talking about us and start talking with us! We are the people whose behavior you’re trying to change. Start talking with us!” Well, a lot of psychiatrists fled the room in horror, but a lot stayed and started talking with the people who had invaded the meeting.

Now, the APA’s conference managers are very smart people. They are not about to let themselves get kicked year after year by some group that wants to invade its meetings to get its message across. So the very next year they invited gay people to be on a panel called, “Lifestyles of Non-Patient Homosexuals,” which we informally called, “Lifestyles of Im-Patient Homosexuals.” They invited six gay people to be on a panel and then to be available at small round tables for discussion. Well, this was an important recognition that there were gays who did not come for therapy. It wasn’t a huge turnout, but it was successful.

Frank Kameny and I ran an exhibit at that convention called, “Gay, Proud, and Healthy: The Homosexual Community Speaks.” We had a good corner location in the exhibit area. We had pictures of loving gay couples, a rack of literature, including a story about a confrontation with an anti-gay psychiatrist, and the word love in great big red letters. I’m sure that was the first time they had seen anything like that at an APA convention. Some people came and took literature. Others made very obvious detours to get past this corner location.

During the convention, a handful of gay psychiatrists talked to us very informally. It turned out that for years there had been a kind of Gay Psychiatric Association—a Gay PA—meeting during the annual APA conference, but it was a very closeted affair. At the time they talked to us, some of these gay psychiatrists were beginning to talk about being more open and doing something within the APA.

The next year Frank Kameny and I were invited by a member of the APA who was interested in this subject of homosexuality to be on a panel along with a couple of heterosexual psychiatrists, including Dr. Judd Marmor. The panel was called “Psychiatry, Friend or Foe to Homosexuals, A Dialogue.” Kay said, “Look, you have psychiatrists on the panel who are not gay. And you have gays who are not psychiatrists. What you’re lacking on the panel are gay psychiatrists, people who can represent both points of view. Why don’t we try to get a gay psychiatrist?” Well, the moderator was perfectly agreeable. But he needed us to find somebody. I made a number of calls, but nobody was quite yet willing to be that public. They feared damage to their careers.

Finally I talked with this one man who said, “I will do it provided that I am allowed to wear a wig and a mask and use a microphone that distorts my voice.” And that’s what he did. He was listed in the program as “Dr. Henry Anonymous,” which is what he requested. He was going to talk about what it was like to have to live in the closet because of the fear of ruining his career. To back him up, I wrote to all the other gay psychiatrists I knew and said, “Please send me a few paragraphs about what it’s like to be a gay psychiatrist in the Association. You do not have to sign it. I will read these at the APA convention.”

It went off marvelously! The house was packed. Naturally, I think the anonymous psychiatrist was the main reason the house was packed. And let’s face it, given the man’s physical size, there were people who were going to recognize him in spite of the microphone and wig. But he was willing to take that chance. He made a very eloquent presentation. Then I read the statements from the other psychiatrists, and that clinched it.

Kay:

Frank Kameny was absolutely against the mask. He wanted it to be up front.

Barbara:

I know, but it went off so well that Frank had to admit afterwards that it was a great gamble. Kay took a wonderful photograph of that panel and you can see the smile on Frank’s face.

I think that panel discussion jolted enough of the gay psychiatrists who were in the audience or who heard about it, to feel they really should be doing something on a more formal basis. The result was the beginnings of an official gay group in the American Psychiatric Association. Because I encouraged them and went to their meetings and helped them along, I like to think of myself as the fairy god mother of the gay group in the American Psychiatric Association.

All of these efforts helped move the APA along much further and much faster on the issue of removing homosexuality from the listing of mental disorders and mental illnesses.

Kay:

This was always more of a political decision than a medical decision.

Barbara:

It never was a medical decision—and that’s why I think the action came so fast. After all, it was only three years from the time that feminists and gays first zapped the APA at a behavior therapy session to the time that the Board of Trustees voted in 1973 to approve removing homosexuality from the list of mental disorders. It was a political move.

When the vote came in, we had a wonderful headline in one of the Philadelphia papers, “20 Million Homosexuals Gain Instant Cure.” And there was a picture of me and a little interview. It was a front page story. I was thrilled. We were cured overnight by a stroke of the pen.

From 1967, when I made my first public lecture to a straight audience, I had to deal with people’s conviction that we were sick simply because they had heard some psychiatrist say so. The APA action took an enormous burden off our backs. We could stop throwing so many resources into fighting the sickness label and begin to devote some of that energy and money to other issues.

Kay:

Even the churches deferred to the shrinks. They abdicated totally. They didn’t say we were immoral. They said we were sick. Now they just say we’re immoral.

Barbara:

But at least that’s arguable. The problem with the sickness label is that it’s supposedly scientific and is therefore not subject to dispute. You can argue with people who say you’re immoral because you can say that there are so many kinds of morality. There are no absolutes. Now that people don’t have the sickness label, they’re coming out with more basic reasons for being against us: “I don’t like you.” “I don’t like the way you live.” “I think you’re immoral.” “I think you’re rotten.” All of that is more honest than this “you’re sick” nonsense.

*Making History is the title of the original 1992 edition of Making Gay History, which was published in 2002. Making History is available as an e-book. Making Gay History is available in paperback.

Making Gay History Podcast – Dr. Evelyn Hooker

In 1956 Dr. Evelyn Hooker, whom Dr. Marmor references in his interview above, presented her groundbreaking study from which she concluded that gay men were no more psychopathological than straight men. Listen to the interview with Dr. Hooker.